Jeanette Andrews Will Add a Dash of Magic to Your Life

Her breathtaking magic performances immerse her audience into an alternate universe that defies the laws of physics. A skilled illusionist, she knows how to enchant the masses as she transforms a rose petal into a solid egg by merely spinning a translucent glass in her hand, and her effortless demonstrations build up to create an impressive body of work, which has landed her performances at world-renowned institutions around the country, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

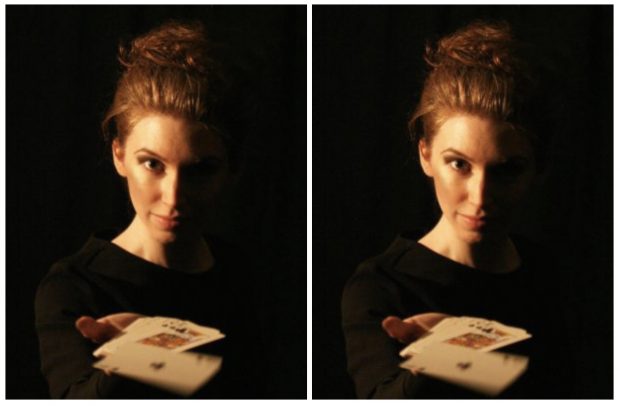

Jeanette Andrews is a contemporary artist and magician distinguished by her formal approach towards her craft. Her performances are hosted with a dark backdrop accompanied by a single, black table on top of which her props lie daintily. She appears in simple, monochromatic outfits under a single spotlight. This majorly differentiates her from other magicians’ styles, such as the flamboyant nature of the Las Vegas stages, where their reliance on special effects is used to divert a large audience’s gaze. Andrews’ minimalistic style steps away from this in its reminiscence of the 19th century “parlor magic,” during which magicians’ shows were viewed in the same light as those of opera singers and ballet dancers.

With her upcoming performance at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago later this Fall, the master illusionist talks to Simone Viteri about turning her performances into thought-provoking experiments, the importance of giving a new spin to the art of the impossible and why we all need a little magic in our lives.

Jeanette Andrews. Photo: Michael Sullivan

What has been your experience in terms of bringing an unconventional medium and presenting it at institutions that are used to displaying more traditional forms of art—paintings, sculptures, etc?

Jeanette Andrews: As a medium, I think it’s so interesting. I mean, I grew up as a magician—I did my first magic performance when I was four. I became interested in bringing magic into these more formal art spaces when I was fifteen and I’m twenty-eight now so it’s been almost half my life that I’ve been working on this particular component. In terms of getting it into these museum spaces, that is a wall and something I’m still figuring out. Having magic in traditional art spaces is hard because I have to really talk to people and make them understand the reasons why I do what I do, my aesthetic, and why it’s relevant. It’s an interesting challenge because it’s so incredibly niche. I’ve spent the last decade trying to build [up] my connections in Chicago. Right now I’m in New York because this is the heart of the arts scene that I haven’t yet explored.

In terms of magicians from the 19th century influencing your work, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin is just one example of a magician at the time trying to bring magic from colloquial street-art to more formal settings. How does your work relate to these influences?

Jeanette Andrews: His work [is] a tradition that I am coming out of, this idea of more formal, parlor magic in terms of its elegance and its scale, and even a lot of the materials that [magicians used] at the time. He did a great job of having magic rise into these formal contexts. As we get into the late 1800s, magic grew to stages in these big theaters where the performances were really well crafted and had a much more narrative view. They were almost these kinds of “playlets.” Going to a magic show used to be a fashionable thing to do and it was very well respected. Over the past hundred years, magic has had this big fall from grace. Max Maven, one of my mentors who’s the most prolific inventor of magic that has ever lived, has a great quote on this that says it better than I can: “The magicians of the 20th century accomplished a great feat, they took something truly profound and rendered it trivial.”

Jeanette Andrews. Photo courtesy of the artist

Aww. That’s so sad!

Jeanette Andrews: I know, right? So from my end, I am fortunate in that I’m looking at magic in a broad sense [where] I see the history behind all of this. I see so much in terms of the technique and the complexity that goes into these things, which you are not supposed to see as an audience. I am participating in something that is so deeply beautiful, complicated, and intricate where I feel like it’s a part of my job to attempt to do it justice.

So, there must be a lot of different stigmas and assumptions that come with being a magician, I’m guessing.

Jeanette Andrews: You’re totally right! There are so many stereotypes associated with magic. For the most part, I don’t fit a single one of them. One is the older, maniacal man who prevails upon women in a certain way, or [the assumption that] magic is explicitly for children. Adults need magic so much more than children because adults can be so jaded and indoctrinated that not a lot is magical to us anymore. If you’re five, a lot of the world is magical, so seeing magic is impressive but it’s a whole different thing as adults, where these ideas of awe and wonder are missing from our lives. The idea of wonder is something that is quite literally vanishing from our hyper-digital age.

Jeanette Andrews. Photo: David Linsell

It’s interesting that you mentioned the concept of people not being aware of their surroundings since that’s such a big part of successfully rendering magic performances.

Jeanette Andrews: It’s an interesting dichotomy because you’re using these loopholes or blind spots in perception to point out that we have these blind spots. I was on the computer as you were calling me looking up directions on Google Maps, and that is more magical than anything I can do. It’s something we rarely stop to think about, the amount of events that have to transpire carefully for our Google Maps to work. That’s a big part of why I do what I do; there are all these incredible things happening around us that we just don’t have time to pay attention to.

Your work relies less on special effects and instead uses a simple, minimalist color palette both on the stages you present on and the props you use. Is this an essential part of connecting your work from magic to art?

Jeanette Andrews: Interestingly, no one has ever asked me this question before so I’m impressed! A big part of why I do this for my performances is to focus the audience’s attention because it’s a lot easier to focus on a prop in the scene if you’re not distracted by anything else. I hear all the time from people watching magic performances, “Yeah, I was watching this show, but it was onstage, far away and there were all these either flashing lights or effects and I really couldn’t tell what was going on.” It’s visual focus, psychological focus, and having kind of singular items that people can really focus on.

In terms of where I gravitate on a personal aesthetic, I am a minimalist. And in terms of color palette both personally and professionally, everything I own is black or white—all of my clothes are black and my entire apartment is white.

Jeanette Andrews. Photo: Nikki Hedrick

Jeanette Andrews. Photo: Michael Sullivan

What do you do if you’re on stage, performing and something goes wrong?

Jeanette Andrews: I’ve learned the hard way not to perform things before they’re ready. It’s like that saying: Wait until you think you’re ready, then practice it for another month and after that maybe you’re ready. In the preparation, I pay attention to details, so I try to think of every conceivable human scenario that can happen and account for it. If someone goes on stage and they fall, and they’re okay, but they knock over everything, what would that look like? I had a guy from the audience help me once, and until he was speaking to me I didn’t realize that he was intoxicated. If somebody cannot understand what you’re doing, how do you divvy up those responsibilities so that the person who’s on stage will feel comfortable? It has to look like this was always the plan, so I’ll say something like, “I need a second person; somebody to hold this.” It’s little things like that that you just kind of learn by doing and correcting in the moment.

Jeanette Andrews. Photo: Jon Whatley

*Featured Photo: Jeanette Andrews by Saverio Truglia